Asked about the austere nature of his monochromatic landscapes of the American Southwest, iconic photographer Ansel Adams once said, “there are always two people in every picture—the photographer and the viewer.”

This statement has a lot of truth to it. A good photographer imbues their photos with a point of view, and if successfully communicated, the person viewing it is also transported into the image, widening their own perspective in the process.

That’s art, in a nutshell. And photography, like any other visual art, has the power to create a greater understanding of ourselves, other people, and the myriad of ways we can perceive the world.

It’s a powerful concept—even strong emotions like empathy or rage can be evoked through the effortless act of glancing at a two-dimensional image.

It’s simple to read Adams’ statement about his own work, and apply it to all photography. However, it does raise some questions.

Like, what happens to a person—a viewer—when all they see is work from photographers who share a common background? And how is a person affected if they never see themselves or their experience represented in photographs? Ultimately, what larger impact does photography have on a culture?

These are worthwhile, complicated questions, but we don’t have to hypothesize the answers. We can simply look around us.

Photography Is Not A Level Playing Field

For a medium that, in theory, is so accessible and egalitarian, it can’t be ignored that not everyone behind, or in front of the camera has been given a voice, representation, or allowed the same opportunities in photography.

By now, it’s well documented how non-white, non-cis-male perspectives have largely been underserved, diminished, and dismissed through the history of photography. Unfortunately, we’re frequently reminded that this problem still exists to this day.

For instance, just last summer, as protests popped up in 140 cities across the country after the police killing of George Floyd, a Black Minneapolis man, there was a glaring absence of Black photographers being hired to cover the events by major publications.

Notably, through early June, all five major newspapers who employee mostly white photo editors (The New York Times, Washington Post, Wall Street Journal, USA Today, Los Angeles Times) featured collections of images from the protests on their front pages, none of which were taken by a single Black photojournalist.

To their credit, after some uproar, these publications made a concerted effort to hire more freelance Black photographers and expressed sensitivity to this issue moving forward. This was the correct move, although it happened after the fact about events where race and discrimination were the central issues.

It must be said that too often in our culture, the white, cis male perspective is given precedence above all others—it is the default gaze through which we are expected to process and experience life. This imbalance has undoubtedly left a tremendous void in how we understand ourselves, each other, and our collective history.

The Past Is Prologue

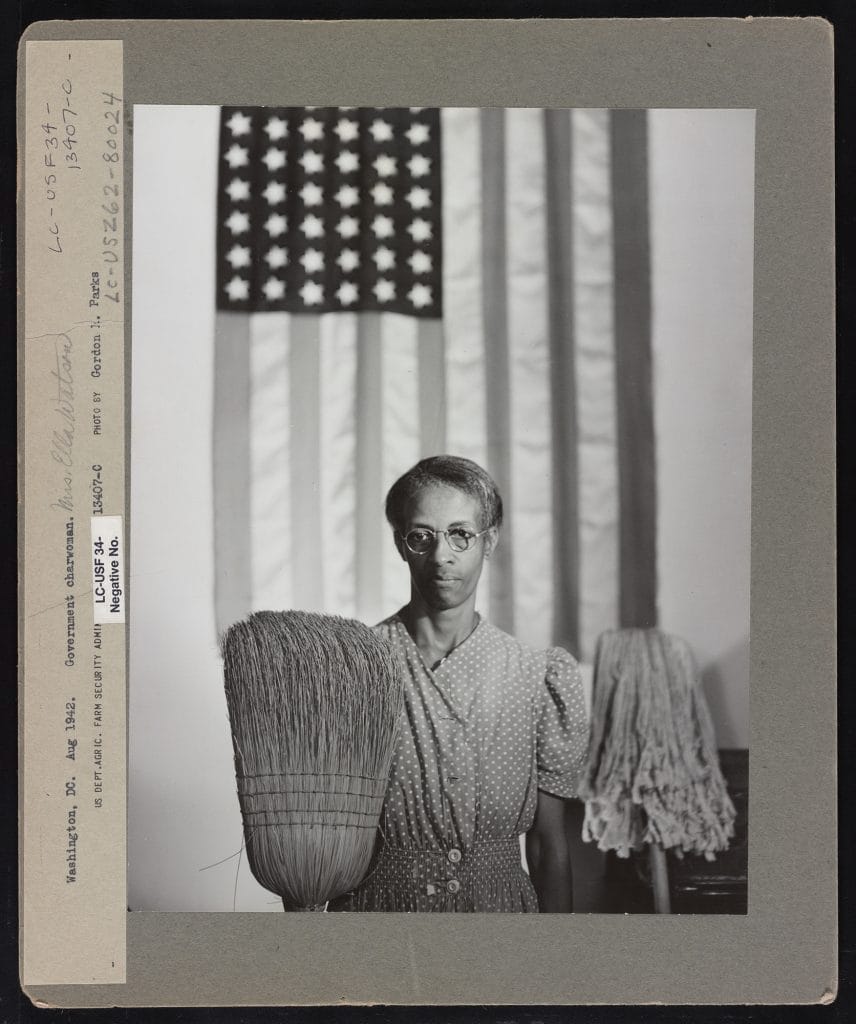

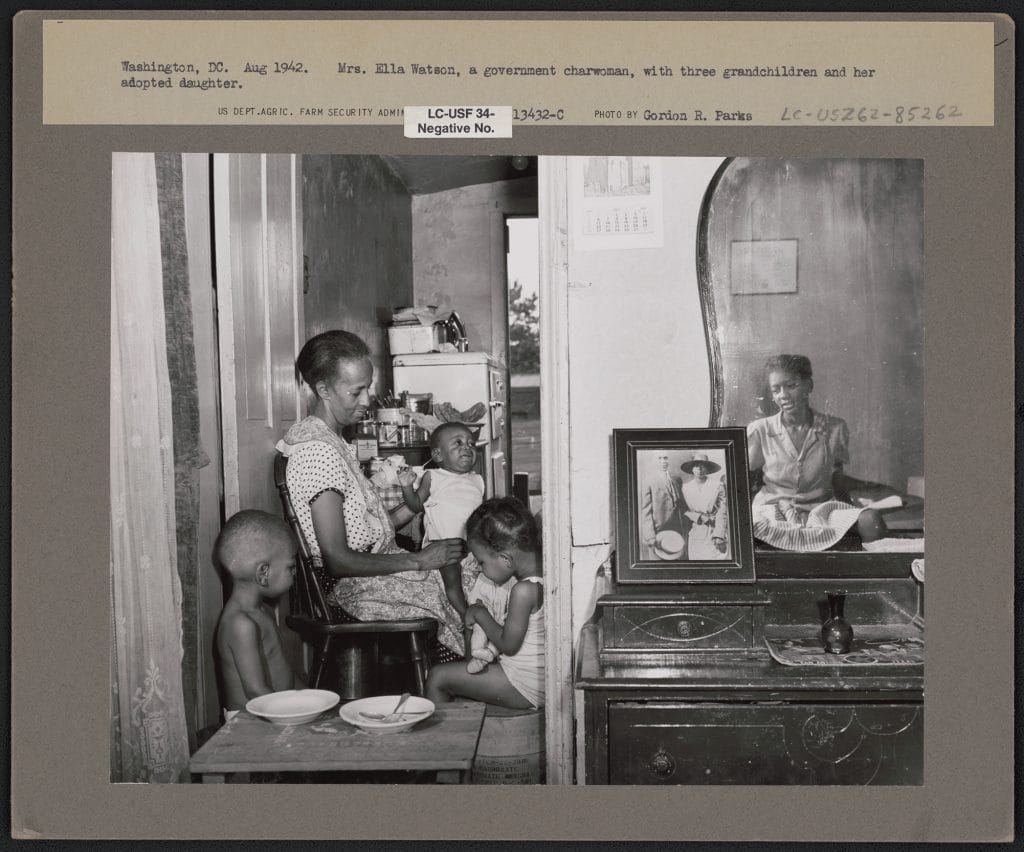

“I suffered first as a child from discrimination, poverty, so I think it was a natural follow from that, that I should use my camera to speak for people who are unable to speak for themselves.” –Gordon Parks

There is a distinct misunderstanding that since there has been progress in this country within matters of civil rights, that we have somehow moved past the problem. This is a dangerous assumption, as it stands to trivialize real, pressing, current issues by comparing them to a horrid past. Additionally, history is often used as a form of anecdotal evidence that justice has already been served.

An example of this that often rears its head in our industry involves one of the greatest photographers of the 20th century, Gordon Parks—a Black man born in 1912 during segregation, the scourge which drew a hard color line around who was permitted to live out the American Dream. His story is often brought up as an instance when a Black photographer was given equal opportunity in their field of work, even during a time of apartheid in America.

But Parks’ success only speaks to his own tremendous talent—he achieved what he did despite the oppressive forces that worked against him, not because he was afforded an equal opportunity.

Gordon Parks was by all measures a master of his craft, as well as an all-around renaissance man—a writer, filmmaker, painter and musician, on top of photographer—a generational talent that left behind a body of work that will be studied and appreciated for generations. When he documented oppressed rural communities, he did it from a place of familiarity.

The fact is that his one-in-a-million ascent happened at a time that saw thousands upon thousands of white men achieve similar success. These men didn’t have to be transcendent photographers to make an honest living. They could be good-to-mediocre, and still follow their chosen career path. They had access to a bevy of platforms to share their point of view, and were often asked to cover communities with which they were not familiar.

No such privilege was afforded to people of color. Like Jesse Owens and Jackie Robinson, Parks had to be one of the greatest ever to even be allowed on the playing field. And even then, he had to play down his own background as to not make waves and stand out.

Through his work photographing rural life for the government, and then for mainstream publications like Life, Parks had to sacrifice so much of himself just to make it in a world that wasn’t built for him. He could’ve easily lost himself tip-toeing through this minefield, but instead, he used it to blaze a path that would empower others.

“In fulfilling my professional and artistic ambitions in the White Man’s world, I had to become completely involved in it … At the beginning of my career I missed the soft, easy laughter of Harlem and the security of black friends around me … Many times I wondered whether my achievement was worth the loneliness I experienced, but now I realise the price was small. This same experience has taught me that there is nothing ignoble about a black man climbing from the troubled darkness on a white man’s ladder, providing he doesn’t forsake the others who, subsequently, must escape that same darkness.” –Gordon Parks

Parks recognized the power of his position. By virtue of representation, both in front of and behind his lens, a cultural catharsis could begin to reach across the land. And he was correct. By being exposed to Parks’ expressive photographs, people from all walks of life were forced to face the social and economic impact of poverty, racism, and discrimination.

The wider public also got to experience the joy, beauty, and dignity of the people in these segregated communities, and could empathize with the humanity that connects us all. Unfettered access to this world only made the photos more authentic and powerful. His work didn’t touch everyone, but it affected enough people to enact change, and that’s how progress has been made—slowly, and by never letting up.

We Are All Witnesses

It’s vital that people from all walks of life be allowed to tell their own stories, and we should value their perspectives by folding them in to our collective experience. Gordon Parks is a relevant example, not as a historical anecdote, but as a stark reminder that the issues from his time still exist today.

Achieving a broader outlook in a society so obscured by its past does not come easy, so achieving a wide perspective comes down to the individual choices we make, and the questions we ask ourselves.

At KEH, we’re a diverse company, and that’s one of our biggest strengths. But there’s always room for improvement, and we’re committed to doing the work. For this reason, we established a Diversity and Inclusion Committee last year, which works internally to ensure all voices are heard within our organization, and we partner with various external organizations within the photographic community.

Luckily, there’s a number of great organizations that are working hard to enact change in our field.

Since I’ve already mentioned the man, it’s worth highlighting The Gordon Parks Foundation, which offers grants, scholarships and education to support the next generation of artists advocating for social justice.

Diversify Photo is currently running a #HireBlackPhotographers campaign, which has created a database of over a thousand Black photographers and videographers from around the world who are available for hire. Plus, they help organize networking, exhibiting, speaking, community-building, and resource-sharing opportunities for their diverse members.

On the topic of representation, Diversity Photos offers stock images and visual content on their site that features a diverse set of subjects, reflecting a more accurate depiction of our global community.

But you don’t have to go out of your way to help. Even something as simple as making an effort to follow a more diverse set of photographers on social media is a meaningful step towards taking in a wider range of views.

I suggest starting with this collection of Black photographers published by See In Black—it includes some of the best photographers working today.

Feel free to add more organizations or resources in the comments below.

Ultimately, if we’re heading down the wrong road, we should go out of our way to find the right path, and we must shine a light so others can join us on that righteous path.

An Obligation To Ourselves

“I’ve been asked if I think there will ever come a time when all people come together. I would like to think there will. All we can do is hope and dream and work toward that end. And that’s what I’ve tried to do all my life.” –Gordon Parks

For someone who loves the medium of photography and its history, it’s painful for me to call out our collective shortcomings, but they must not be ignored.

Admitting that this is an ongoing problem is a step in the right direction, and if we’re going to get anywhere, those that have benefited from discrimination carry the burden to fix it.

During Black History Month, and most importantly, when the spotlight is dimmer on these issues throughout the year, we must admit to ourselves, and each other, that a large portion of voices are still underserved and underrepresented. There are structural features in this industry—and in all levels of society—that perpetuate racial inequality and injustice.

It’s up to us to do better. Otherwise, we all suffer the consequences of a smaller, narrower, poorer existence.

Main image: Luca Eandi “A smiling woman walks by a mural of Gordon Parks’ Invisible Man.” June 23, 2019. Atlanta, GA.